| Caithness.Org | Community | Business | Entertainment | Caithness... | Tourist Info | Site Map |

• Advertising • Chat Room • Contact Us • Kids Links • Links • Messageboard • News - Local & Scottish • News - UK & News Links • About / Contact Us • Submissions |

• Bookshop • Business Index & News • Jobs • Property For Sale • Property For Rent • Shop • Sutherland Business Index |

• Fishing • Fun Stuff • George, The Saga • Horses • Local Galas • Music • Pub Guide • Sport Index • What's On In Caithness |

• General Information • B & Bs • Backpackers • Caravan & Camping • Ferries • Getting Here • Holiday Letting • Hotels • Orkney • Pentland Firth • Sutherland • Taxis |

| N E W S F E E D S >>> |

|

History of Caithness |

|

Index & Introduction Page One Page Two Page Three Page Four Page Five Page Six Page Seven Page Eight |

|

Civil And Traditional Chapter 1 - Page Five |

|

In going over the ruins, two

striking objects present themselves. The one is a large stump of

wood projecting from a part of the wall

in the tower, which is said to be a portion of

the gibbet used in the execution of criminals, or of such unhappy

wretches as had incurred the Earl’s displeasure. The other is the

subterranean cell in which prisoners were confined. This horrid

dungeon, partly formed in the rock, had but one small aperture

opening on the bay, but beyond the reach of the captive, which

afforded just light enough to reveal the gloom that pervaded the

interior. The view of it forcibly suggests to the mind an idea of

the oppressive tyranny and cruelty of former times. No situation can

be conceived more miserable than that of the unfortunate beings who

were shut up, it might be said, without light or air, many of them

for years, in this damp and noisome pit, where, in the words

of Byron’s prisoner of Chillon

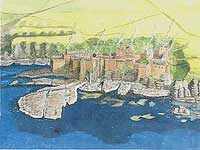

— A drawbridge over a natural chasm in the rock connected the two castles, the new and the old, together. Hence, in the case of an attack, if the one stronghold was in danger of being taken, the besieged could easily retire into the other. On the land side, in addition to this goe, both were protected by a deep and broad artificial ditch, cut across the neck of the peninsula, over which was the main or principal drawbridge, which afforded access through an arched passage to the court of Castle Sinclair. The situation of this double fortress was naturally strong; and before the invention of artillery, it might with its well-constructed defences, be considered impregnable. The castles seem to have been inhabited till about the year 1690. As the country became more settled and civilised, the principal gentry began to desert their wild abodes on inaccessible rocks and precipices overhanging the sea, and to erect comfortable houses of modern construction in more agreeable situations. Sinclair and Girnigoe shared the fate of similar strongholds along the coast. After being abandoned, they gradually went to decay; and time and tempest did their work upon them, until they have become the striking ruins which they now exhibit, conveying a moral more impressive than a thousand homilies on the perishable nature of all earthly grandeur. The ivy which proverbially clings to decay, and with its green mantling foliage imparts even to the hoary ruin a pleasing look, is here totally wanting; and the bare delapidated walls, where nothing is seen but the rank weed, and no sounds are heard but the scream of the sea-fowl and the moan of the weltering billow, present one of the gloomiest of pictures, and fill the mind with feelings of a melancholy kind. More On Sinclair & Girnigoe Castles On the north side of the bay, opposite Sinclair and Girnigoe, stand the ruins of the castle of Keiss, anciently called the “fortalice of Raddar.” It belonged also to the Earls, and was the favourite residence of the second Earl George. The castle and lands connected with it became latterly the patrimony of George Sinclair, who disputed the titles with Glenorchy. Dunnet Bay may be said to commence between Holbornhead and the opposite headland of Dunnet. It forms a deep indentation, somewhat in the shape of an oblong, and runs down towards the south-east for the space of nearly four miles. Its breadth across is about two miles and a half, and it is completely land-locked on the south side by the low rocky shore of Castlehill and Murkle, and on the north or Dunnet side by the lofty wall of precipices formerly mentioned, amongst which the bluff bold brow of Dwarwick rises up conspicuously.

When roused by a heavy westerly gale the bay, from the tumultuous agitation and magnitude of the breakers, presents a sublime spectacle. The huge, long, white-crested billows, lashed into fury by the storm, seem to chase each other; and as they hurry on towards the beach, burst with astounding force—the broken surge churned into foam rushing up along the sand with the speed of a race-horse, and then rushing back again as rapidly, as if sucked down by the raging flood. Here and there a few gulls, perhaps in quest of prey, may be seen vainly struggling with the blast, while from all sides of the bay is heard one continued roar like that of the loudest thunder. Caithness contains a multitude of small lakes. In the parish of Halkirk alone, there are no fewer than twenty-four. The three largest in the county are the loch of Watten, the loch of Calder, and Lochmore. The first is about three miles in length, and about a mile in breadth. But the most celebrated loch in the county is that of Dunnet, or St John’s, which lies a few hundred yards to the north of the church, and is little more than half a mile long, and one-fourth of a mile broad. In the olden time it was greatly famed for its supposed virtues in curing all kinds of chronic and lingering disorders; and, in consequence, people resorted to it from all parts of the county, and even from Sutherland and the Orkneys. There were particular times for visiting it, viz., the first Monday of each quarter of the year. The summer quarter was on many accounts considered the best. The patient had to walk round the loch early in the morning; and if his strength did not permit him to do so, he was carried round it. The ceremony which he had to go through consisted in washing his face and hands in the lake, and throwing a piece of money, commonly a halfpenny, into it; and, if he would derive any permanent benefit to his health, it was absolutely necessary that he should be out of sight of it before sunrise. It is difficult to account for the origin of this superstition, for superstition it undoubtedly was. The waters of the loch do not seem to possess any healing or medicinal qualities. There was anciently on the east end a Catholic chapel dedicated to St John, and it is extremely probable that the alleged virtues of the loch may have been conferred on it by the priests, and converted by them into a source of pecuniary emolument. After the subversion of the Popish religion in the district, the practice still maintained its ground; and the money which was formerly given to the church was now thrown into the consecrated waters of St John. At present it is seldom visited except by a few valetudinarians of the lowest class from the more remote parts of the county. The people living in its immediate neighbourhood have no faith whatever in its healing virtues, and only laugh at the superstition. It is quite possible, however, that from the united influence of imagination, change of air, and exercise, several of the patients may have been not a little benefited by their jaunt to the “ halie loch.” The only hilly parish in Caithness is Latheron, especially that part of it immediately bordering on Sutherland, where majestically tower up the long alpine ridge of

* There is a loch in Strathnaver called Lochmonar, which the common people believed to possess tbe same wonderful healing qualities as the one at Dunnet; and what is curious enough, tbe ceremonies whicb the patients had to go through were the very same at both lochs. There is an old tradition (evidently a monkish invention) which says that on St Stephen’s day its basin was occupied by a pleasant meadow and that on St John’s day the meadow was covered with water. This story of its origin, so akin to the marvellous, would, among a simple and credulous people, very naturally heighten their belief in its supposed curative powers.

Index & Introduction |