| Caithness.Org | Community | Business | Entertainment | Caithness... | Tourist Info | Site Map |

• Advertising • Chat Room • Contact Us • Kids Links • Links • Messageboard • News - Local & Scottish • News - UK & News Links • About / Contact Us • Submissions |

• Bookshop • Business Index & News • Jobs • Property For Sale • Property For Rent • Shop • Sutherland Business Index |

• Fishing • Fun Stuff • George, The Saga • Horses • Local Galas • Music • Pub Guide • Sport Index • What's On In Caithness |

• General Information • B & Bs • Backpackers • Caravan & Camping • Ferries • Getting Here • Holiday Letting • Hotels • Orkney • Pentland Firth • Sutherland • Taxis |

| N E W S F E E D S >>> |

|

Caithness Field Club Bulletin |

|

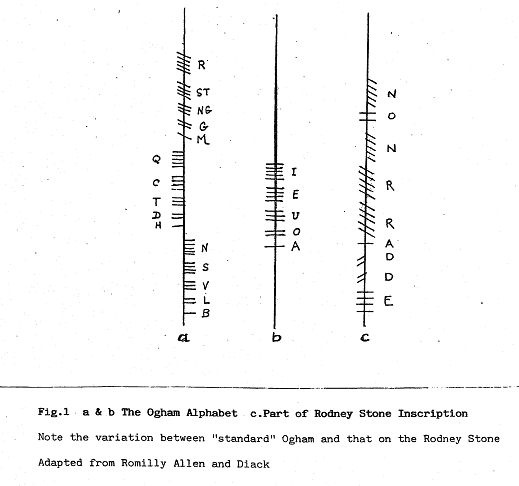

The Rodney Stone (by Ian Keillar) Arising from the Field Club�s Weekend visit to Elgin, Ian has kindly provided this article as background. On the 12th of April 1782, off the Saints Islands near Dominica, Admiral George Brydges Rodney decisively defeated the French fleet under Count de Grasse and thus secured the British possessions in the West Indies. The fact that Rodney's victory was due to a fortunate change in the wind does not detract from his achievement. The admiral's fame and name is allegedly the reason why the Pictish Cross, now in the grounds of Brodie castle, is known as the Rodney stone. The story, hallowed by much retelling, is that in 1781, a new kirk was being built at Dyke and during the excavations for the foundations, a number of coins were found and the Pictish cross-slab was uncovered. After being used as a grave stone it was subsequently set up in the village to commemorate Rodney's victory and some time in the early 19th century it was moved to Brodie castle and its name moved with it. And so it has remained to this day. But not all agree with the accepted story. Bain1, never one to be too particular with the facts,states "It...is known as Rooney's Stone from the circumstance that for a time it lay neglected in the garden of a man of that name." A more reliable and recent source, McKean2, referring to the stone, writes "although it is said that the name of the sexton who dug it up was Rotteney." Alfred Forbes3, late provost of Forres, comments "This is also incorrectly called the Rodney stone." However, the worthy provost neglects to tell us what the stone should correctly be called. Douglas4, the Forres historian cautiously states "Some suppose that the stone commemorates Rodney's victory over Count de Grasse." Others have suggested that the stone is named after an anonymous rat catcher, referred to only by his profession, as Rodenty or Rootney. A trawl through the Dyke parish records of births from 1761 to 1819 reveals no Rodneys, Roomeys or similar being born. The nearest is a Robertson and a Rorie. Brodies and Forsyths abound but nobody with a name resembling the shadowy rat catcher or sexton was fathering a child. The marriage register for the same period was also examined with the same result. Of course this does not mean that a person with the wanted name did not live at Dyke. It may be that he was neither born nor married there and had no children, or I may have missed the name in the sometimes difficult to read registers. However, the negative search result strengthens the supposition that the stone was actually named after Admiral Rodney. Near contemporary reporters not only do not give the stone a name, but completely ignore it. Dunbar5, the parish minister in 1793, slavishly answers all of Sir John Sinclair's questions for the Statistical Account and while he relates the account of the finding of a hoard of silver coins when digging the foundations of the new kirk, he does not mention the presence of a large slab of engraved sandstone. Writing five years later, Grant and Leslie6, follow their fellow cleric Dunbar, even using the same wording, and do not mention the cross slab. Even more surprisingly, some 25 years after his earlier publication, Leslie7 the erudite and inquisitive minister of St. Andrews, Lhanbryde, does not mention the stone in his description of Brodie castle. It is not until 1845 that Aitken8, writing in the New Statistical Account, makes the first, so far discovered, printed account of the stone. "Near the northern approach to Brodie House, is a sort of obelisk, about six feet high, forming a parallelogram. On one side is a cross, elaborately carved, and on the other a number of rudely sculptured fabulous animals. It was found in digging out the foundations of the present church, and was claimed by some of the parishoners as a grave-stone, a purpose for which it was obviously never designed It was put up in the village in commemoration of Rodney's victory over the Count de Grasse, and from that circumstance received the name of Rodney's Cross. A few years ago it was removed to the Park of Brodie." As Aitken's writings are the earliest in time, it is reasonable to assume that they are the most reliable. Dunbar may have been inhibited from mentioning the stone as it was being claimed by some of his parishoners for use as a grave-stone. Grant and Leslie copied Dunbar, either through ignorance or laziness, although it is surprising that Leslie makes no mention of the stone in his Antiquites and Curiosities of Moray, which appeared in 1823. William Leslie, the only minister to write the Old and New Statistical accounts of his parish, was a widely read man with an enquiring mind and a reasonable explanation for his ignoring of the Rodney Stone is that when he was writing his Antiquities the stone was still being used to cover a grave at Dyke. So, when Aitken states "A few years ago it was removed to the Park of Brodie"; this would indicate some time, say, between 1820 and 1840. However, Alexander9, in his delightful Antiquities of Moray publishes an engraving of "Stones in the Parish of Dyke" by Dick Lauder and dated 1831. The stone is shown considerably deeper into the ground than it is at Brodie so perhaps the flitting took place between 1831 and 1840. The Brodie Estate papers are still held in the castle so an approach to the National Trust may result in clearing up the minor detail of when the stone was translated from Dyke to Brodie. Despite its size and intricate carvings and its somewhat battered Ogham inscription, little has been written about the stone. Romilly Allen10, describes it as "an upright cross-slab of grey sandstone, of rectangular shape, 6 feet 4 inches high by 3 feet 5 inches wide at the bottom and 3 feet 2 inches wide at the top by 5 inches thick at the bottom and 4 inches thick at the top, sculptured in relief and inscribed with incised letters on two faces..." The incised letter are not in Roman characters but in Ogham. Ogham is an alphabet ,based on the Roman, but using strokes or grooves, cut across a base line, to represent the letters (see Fig. 1). The alphabet was developed in Ireland for use on stones where it is considerably easier to cut than the Roman alphabet. It came to Scotland with the Irish some time after circa 500AD but no Gaelic inscriptions survive. The language used by the Ogham stone cutters in what is now Scotland is completely unknown. Here and there a personal name can be deciphered, but most of the meaning is speculative. This speculation varies from the learned to the ridiculous, although these categories are not completely exclusive. George Moore11, was one of several who combined great learning with an excess of credulity. A Doctor of Medicine and at ease with Sanscrit and Hebrew and with a fair knowledge of Arabic and Chaldean he proved, to his own satisfaction, that the Ogham inscriptions were inscribed by othodox Buddhists in Sanscrit This was in 1865, but some of the more modern experts are not much better. Certainly their various interpretations can give cause for wonder. On the Brodie Stone it is possible to decipher the Ogham characters which, when transliterated into Roman characters, read EDDARRNON. This word also appears on a stone in Fife and is assumed , tentatively, by Diack12 and more positively by Knight13, to be analogous with ETHERNAN, a Pictish saint who died, somewhere in the North East, on 2nd December 668. So, just as we claim St. Giles to be the patron saint of Elgin, can we claim St. Ethernan to be the patron saint of Dyke? Alas, the Medieval sources are silent about this, and the modern ones are suspect. McKay14, in 1981, writes "They say that Dyke had a great and far-travelled St. Moloug as patron saint, and that a well at Dalvey with healing qualities was dedicated to him." Unfortunately Miss McKay does not say who "They" were. However the fact that Dyke does not have a medieval patron saint increases the possibility that it may have a connection with an earlier Celtic missionary. In the Brodie papers15 there is documentary evidence of a chapel dedicated to St Ninian, but this appears to have been located in the Culbin at some distance from Dyke. Any suggestions, with evidence, for the name of the patron saint of Dyke would be much appreciated The slight possibility that ETHERNAN could be connected with Dyke is based on the assumption that the Rodney stone originally came from Dyke. We know that it was moved in historical times but could it have been moved earlier? In Moray, carved stones have a record of going walkabout. Not everybody is aware that the Altyre stone now stands several miles from its original position. The Pictish stone in Elgin cathedral came from the High Street of Elgin in the early 19th century, but it was quarried and presumably carved at Keith sometime in the first millennium. If a 1.5 tonne stone could be moved 18 miles from Keith, including a crossing of the Spey, should we not also consider the possibility, however slight, that the Rodney stone, all two tonnes of it, came from elsewhere? When the wind suddenly changed off Dominica on 12th April 1782 thus allowing the British ships to close with de Grasse, where the close range quick firing Carron guns caused so much devastation among the French fleet, little did Admiral Rodney know that two hundred years later his name would be more associated with a carved stone than with his famous victory. However, Rodney's sea victory was decisive and easily understood. The same cannot be said about the stone named after him.

References |