| Caithness.Org | Community | Business | Entertainment | Caithness... | Tourist Info | Site Map |

• Advertising • Chat Room • Contact Us • Kids Links • Links • Messageboard • News - Local & Scottish • News - UK & News Links • About / Contact Us • Submissions |

• Bookshop • Business Index & News • Jobs • Property For Sale • Property For Rent • Shop • Sutherland Business Index |

• Fishing • Fun Stuff • George, The Saga • Horses • Local Galas • Music • Pub Guide • Sport Index • What's On In Caithness |

• General Information • B & Bs • Backpackers • Caravan & Camping • Ferries • Getting Here • Holiday Letting • Hotels • Orkney • Pentland Firth • Sutherland • Taxis |

| N E W S F E E D S >>> |

| More Everley Broch Pictures 2001 | More Everley Broch Pictures 2002 | ||

| Caithness Field Club At Everley Broch | |||

|

Caithness Field Club Bulletin |

|

Excavations at Everley, Tofts,

Freswick 2002: Introduction This brief note offers some thoughts on the excavations of a multi-period Iron Age mound at Everley, Tofts, near Freswick. The work is part of a wider project that aims to pull the rich archaeological record of Caithness into current discussions of the Scottish Iron Age; while interest in other areas has grown markedly over the last 30 years, with a few exceptions, Caithness continues to be largely overlooked. A report on the first year's excavations was published in last year's journal. This summary builds on this, outlining some findings and thoughts arising from this summer's excavations. As work only finished a matter of months ago, and no detailed post-excavation has yet taken place, what follows should be taken only as initial thoughts garnered over the 5 enjoyable weeks in Caithness. Fuller, and more justified, interpretation must await further analysis. At the outset, I would like to express my thanks to the many Caithness people who have supported our work and made the excavation so enjoyable, particularly Jack Dunnet, Nan and George Bethane, Meg Sinclair and Paul Humphreys. Special mention must be made to the ever-accommodating landowner and friends Ian Angus, Linda and Alex Norburn and family. The Caithness Archaeological Project

and Everley, Tofts.

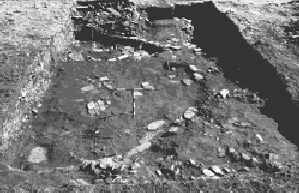

Excavations began at Everley, Tofts, a grassy mound, 5 miles from John O�Groats, last summer. Barry excavated the site in 1897. However, little is known of the site as few records were kept. The aim of our investigations was not to re-excavate the whole site. Instead emphasis was on evaluation, and on opening small areas. In particular we wanted to evaluate the nature of Barry�s investigations, to get inside his head: to study his working methods, his attitudes to artefact retrieval, and his wider reasons for excavating the sites. Doing so, of course, has an additional benefit: it allows us to evaluate whether Barry left us any remaining, untouched archaeology. The lack of work in Caithness since Barry�s time means that we have little understanding of the date and nature of these sites. It was hoped that Barry�s sites would allow us a rare glimpse into the date and use of Iron Age roundhouses. In this summary I want to concentrate mainly on the excavations in the roundhouse interior. As is typical with much research, in order to get to the information you want you have to first wade through piles of rubbish: 50 tonnes to be precise, which had been dumped on the roundhouse since Barry left! However, after many days of removing fertiliser sacks, broken teapots and discarded picks, we found the point where Barry stopped his investigations: in particular we found the remains of a badly denuded roundhouse structure (figure one). As figure one highlights the site has been heavily robbed over the last hundred years, resulting in the visually unimpressive remains of the site. However, we still uncovered the remains of architecture, including paving, tanks and hearths and associated occupation deposits. Although uncovering someone else�s work, which has also been messed around with over the last century, may not seem that rewarding it has had important bearing on our overall study. Getting inside Barry's head

Re-excavation also demonstrated that Barry was not interested in excavating the entire roundhouse either inside or outside. There are still significant untouched deposits in the interior. Outside the broch we also found one of Barry�s characteristic wall-chasing trenches, its shape mirroring the curvature of the broch, room enough for one man to investigate with his pick and spade. Again, Barry did not investigate these fully. Barry was interested solely with finding the broch�s shape and any internal fittings, and then stopping. These points combine to suggest that Tress Barry treated his excavations as a way of uncovering interesting structures or points of discussion to show on his estate, perhaps places to take friends or visitors. Barry, then, was not like other contemporaries. He was not interested in fully investigating an Iron Age house or village, reluctant to collect all of the material, reluctant to publish. Lest there be any doubt, if you visit the many monuments scattered around the Caithness landscape built by Barry to commemorate his own excavations - Nybster is a good example - you will find that one of the key building materials are often the stone objects, particularly querns, found during his excavations! Perhaps Barry�s main reason for digging any of the sites was simply because they were on his land. That he owned one of the densest Iron Age landscapes in Scotland appears to have been of little academic interest to him. The re-excavations of Everley have, therefore, given us much needed insight into Barry�s attitudes that have a large bearing on our analysis of the artefacts. Indeed, we are perhaps lucky to have as many objects in our museums as we do.

The wider picture Barry left a significant amount of archaeology behind. Although we have, literally, only scratched the surface, we have recovered a range of material from previously untouched, dateable deposits. This material will allow us to build up new understandings of the material culture of the area and the lifestyles and habits of the Iron Age inhabitants in the area. One of the good things is that we have recovered a sizeable and varied stone assemblage, some which can be easy paralleled, others that can�t. We have also recovered a fair size and range of pottery. Our limited evaluation suggests that understanding the material culture of Caithness may begin to improve in the future. Our evaluations also suggest that the deposits which Barry left us in the roundhouse interior may be close to primary: the roundhouse wall and associated deposits do not appear to go down much deeper. Indeed, outside the entrance, the deposits are particularly shallow and apparently built on top of an earlier ard-marked ground surface (figure four). Although we must await radiocarbon dates for confirmation it appears that Barry has left us untouched deposits which may relate to the initial occupations of an Iron Age roundhouse. As I have stressed throughout this paper, our present emphasis is on evaluation: we have barely touched the surviving deposits. However, if we were to the benefits for understanding Iron Age Caithness society are obvious. As last year's paper highlighted Barry also left us valuable information outside the roundhouse and these must not be ignored. We continued excavations of our putative Late Norse building and investigated other external areas, which may be Iron Age settlements. Again, such periods in Caithness are little understood and we now have a good opportunity to study them. If nothing else, excavations outside the roundhouse show that Everley was a long-lived site for over a thousand years.

Conclusion This brief note has highlighted some of

the key thoughts garnered during our excavations this summer. Acknowledgements The Caithness Archaeological Project is a joint collaboration between the National Museums of Scotland and the Department of Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, without whom the project could not survive. Welcome support has also been provided by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the Russell Trust, the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, the Catherine MacKichan Bursary Trust and Highland Council. References Anderson, J 1901 �Notice of nine brochs along the Caithness coast from Keiss Bay to Skirza Head, excavated by Sir Francis Tress Barry, Bart, MP, of Keiss Castle, Caithness�, Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 35 (1900-1), 112-48. Heald, A & Jackson, A 2001 �Towards a new understanding of Iron Age Caithness�, Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 131 (2001), 129-47. |